As I sit down to begin writing this, it is Thursday, October 6, and I have long been planning the launch of this new platform on the first day of 2023. In light of recent events in Iran, however, I feel compelled to say something immediately. I have been holding off on commenting on current events or publishing anything, but this - at least - cannot wait.

Some Context & Comparison

It is too early to tell what the significance or consequences of the protests in Iran will ultimately be, but it is clear that something significant is happening. It is important to note that the tactics being employed by the regime are straight out of their standard playbook for handling significant civil unrest, and that these tactics have been used very successfully to quickly and effectively suppress mass protests in the past.

In the most recent instance, in November 2019, the regime similarly shut off all access to the internet and dispersed public protests with deadly force, killing as many as 1,500 civilians. This was sufficient to all but crush the unrest, and the main phase of the protest lasted barely a week as a result.

November, 2019

The protests in 2019 occurred in a context of long standing grievances, pro-democracy activism, and isolated one-day protests and strikes. The large and protracted unrest of November, however, was triggered by the announcement of a dramatic increase of fuel prices which were announced early on the 15th and touched off protests that day which occurred in 37 cities.

The protests quickly escalated, spreading to more than 100 cities (significantly, to the capital, Tehran, and other major cities which had been untouched by the first day of protests) by the 16th — the second day — and incurring a swift and severe response from the regime. By the end of that second day, State news agencies were reporting that over 1,000 protestors had been arrested, access to the internet had been shut off for the entire country, and security forces fired on protestors with live ammunition, killing many of them.

By the 21st, the 7th day since the protests began, Iranian authorities were declaring that the unrest was over and began partially restoring internet access. The New York Times, among others, questioned whether the regime was downplaying the extent to which unrest still smouldered, but if the protests were not yet decisively crushed, security forces certainly had the situation well in hand. The times reported1:

“Three residents of Tehran reached by phone said that the affluent northern part of the city was quiet, but that unrest persisted in middle-class and working-class neighborhoods. They said the capital had the appearance of a heavy security zone, with swarms of anti-riot police on motorcycles and Special Forces lined up on nearly every major road. Plainclothes Basij militia members were also out on the streets.”

September & October, 2022

Current Protests Not So Quickly or Easily Crushed

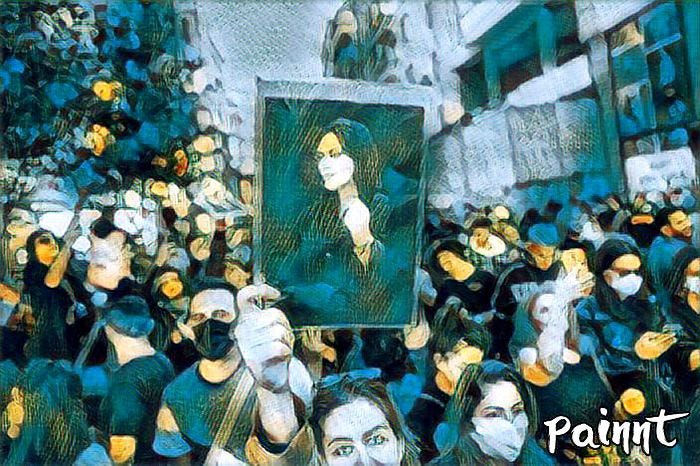

By comparison, the current protests which began in September are proving to be surprisingly enduring. As I write this, the protests are in their 19th day, despite an even greater crackdown by the regime. On September 30, Amnesty International disclosed that it had obtained leaked documents from September 23 in which the commander of the armed forces in Mazandaran province instructed security forces in all towns and cities in the province to “confront mercilessly ... any unrest by rioters and anti-Revolutionaries.”2

Iranwire, “a collaborative news website run by professional Iranian journalists in the diaspora and citizen journalists inside Iran,” reported yesterday that a reliable source “[had] confirmed the use of military weapons, drones and helicopters by Iran's military and security forces.”3 At the same time, the Iranian military has been carrying out attacks against Kurdish regions of Northern Iraq; Iran’s Kurdish minority has played a prominent role in the protest, owing to the fact that Mahsa Amini - whose death catalysed the protests - was a Kurdish woman.

As in 2019, security forces have attempted to disperse protestors using deadly force, and the death toll is mounting. On October 2, according to Reuters4, Iran Human Rights (IHR) reported 130 confirmed deaths, but the true figure is likely much higher. Figures like the one from IHR quantify only those deaths of known individuals which can be definitely and independently verified, and Iranian authorities have been known to engage in widespread attempts to systematically disrupt the ability of independent observers to collect this information and of family members to report or provide evidence of the deaths of loved ones.

A look at the number of deaths reported - as distinct from confirmed - by various sources in different incidents and regions may begin to suggest the true extent of casualties. Radio Farda – a division of Radio Free Europe operating out of Tehran - reports more than 80 deaths in Zahedan alone, citing Baloch activists.5

In addition to viciously beating protestors with batons, including many who were already detained, “delivering dangerous head and neck strikes and punching, kicking, pushing and delivering forceful blows with batons causing the victims to collapse to the ground,” Amnesty International “also documented sexual assaults and other forms of genderbased and sexual violence, including grabbing women’s breasts and violently pulling women from their hair in reprisal for removing their headscarves.”

There have also been mass arrests, and particularly of journalists, activists, and students. Iranwire reported that 300 students were arrested in just Tabriz, on Saturday alone. The Committee to Protect Journalists reports that thirty-six journalists are known to have been arrested in connection with the protests6, including the female journalist who broke the story of Mahsa Amini's death in the custody of the morality police, Niloufar Hamedi, who writes for the Iranian daily Shargh.7

What is the Significance?

“‘This is not a protest anymore. This is the start of a revolution,’ chanted a group of students outside the science department of Mashhad University, as the unprecedented protests in Iran over the death of Mahsa Amini continued into their 18th day on Monday.”8

Many analysts and commentators have argued that the current protests have much broader public support than comparable protests in recent years. The requirement for women to wear the hijab has become a major part of the iconography of the protests, but it is symbolic of the regime's socially repressive policies and authoritarianism more broadly, and the protests have harnessed the dissatisfaction and grievances of a diverse cross section of the Iranian population. As Patrick Wintour, the ‘Diplomatic editor’ at the Guardian noted, “it’s hard to find someone in Iran who hasn’t been harassed at least once by the ruling clergy in some way.” Be that as it tmay, women are clearly at the forefront of the protests, a fact of some significance itself.

Further indications of the extent of support for the protests include the widespread participation of high school girls9, the visible solidarity between Iranian women of older generations with these young firebrands, the significant participation of university students, and to a lesser degree the outspoken support even from university faculties. Footage circulating online in recent days allegedly shows a scene from a girls school to which members of the Basij, the greatly feared paramilitary volunteer force, had apparently been invited to speak to the students about the protests. The young students responded by removing their head coverings and chanting, “get lost, Basiji,” displaying a level of courage which is quite simply staggering.

What this - and like occurrences - also demonstrate is the frankly revolutionary tone of the protests and mood of the country. Reuters recently quoted Kasra Aarabi, “the Iran Program Lead at the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change,” as saying that “one striking similarity the current protests have with 1979 is the mood on the streets, which is explicitly revolutionary ... They don't want reform, they want regime change.”10 This is not to suggest the protests have any genuinely revolutionary potential; any realistic analysis of the situation would have to recognize that the possibility of such an outcome is unlikely in the extreme. But it is nonetheless significant that such large numbers of Iranians not only feel this way - that they strongly desire the end of the regime - but are boldly expressing this sentiment publicly, both explicitly and symbolically. If we ever see an end to this reign of tyrants, which has ground the Iranian people’s potentialities and self-realisation under its proverbial heel for so long, it will certainly have to begin with Iranian’s coming, en masse, to the firm conclusion that that is what they want and what their country needs.

¡

It has been more than sufficiently emphasised in the commentary of academics and analysts in the last few weeks that popular protests are unlikely to force systemic change in authoritarian countries like Iran. But there are reasons for hope.

Firstly, the protests may serve as a barometer. As I have suggested, the events of the past few weeks reflect fissures beneath the surface of Iran’s socio-political landscape. Daniel Brumberg, writing for the Arab Center Washington DC, argues that the protests are rooted in “a much broader crisis of legitimacy that was born of the yawning gap between state leaders’ claims and the everyday reality of economic difficulties and endless repression by morality enforcers and other security bodies.”11

Secondly, the protests will likely galvanise and inspire Iranians. Consider what the last few weeks must mean to the Iranian people themselves. They have been witnessing and participating in these scenes; scenes of defiance, of self-emancipation, scenes of solidarity and of incredible courage; and scenes, no less importantly, of armed thugs try to snuff out the hope and the courage and the solidarity before their very eyes, beating and stomping and shooting the bearers of their deepest hopes, dragging them to vans to be hauled to Evin prison, to be held incommunicado, to be humiliated and starved, and above all to be silenced.

For weeks now they have watched and have played in this drama. Be assured, this means something to them; indeed, especially to the young, this means everything to them. The protests will be brought under control, and life will have to return to some facsimile of ‘normality’. A tense peace - the ‘peace’ of the conquered - must then prevail. But there will be no going back. A young Iranian girl who has felt the thrill of telling the morality police to fuck off, in chorus with her classmates, right to a man from Basij’s face and right there in her classroom, will never be the same as she was before these protests began. A young woman who has stood with multitudes in daylit streets and, whilst under assault by the security forces, burned her head covering and chanted “Woman, Life, Liberty!” will never be the same. Thousands of men and women who have faced gunfire and continued advancing, who have known the possibility of death and found they would face it, and that having made it home in one piece at night they would get up the next day and face it again, and again, will never be the same.

Yes, they will be changed. They will certainly be hardened, They will have developed a group identity, and a solidarity forged in, tested by, fire. With a little luck, they will have learned a thing or two, and developed some knowledge of strategy and activism, and not merely the nerve to act. They may even have made associations and networks. I hope very sincerely they will continue to do so, covertly, once the protests end. One of the more rudimentary bases for affecting real change, Brumberg writes, is developing “inspirational leaders who can transform disparate protests into organised collective movements.”

‘Iran Declares Protests Are Over, but the Evidence Suggests Otherwise’, Farnaz Fassihi and Rick Gladstone, The New York Times, November 21, 2019.

‘Iran: Leaked official documents ordering deadly crackdown highlight need for international action’, Amnesty International, September 30, 2022.

‘Day 18: Child Victims, Hundreds Arrested and International Support’, Roghiyeh Rezaei, Iranwire, October 5, 2022.

‘Events in Iran since Mahsa Amini's arrest and death in custody’, Reuters, October 5, 2022.

‘Increase in the number of victims of Zahedan shooting to "more than 80 dead, including two children"’, Radio Farda, October 4, 2022.

‘Name of journalists arrested in Iran’s anti-state protests’, Committee to Protect Journalists, September 29, 2022 (Updated October 6).

‘Woman Take Center Stage in Antigovernment Protests Shaking Iran’, Vivian Yee and Farnaz Fassihi, The New York Times, September 26, 2022.

‘Are the protests in Iran just doomed to flare and then be crushed?’, Patrick Wintour, The Guardian, October 6, 2022.

‘Iranian schoolgirls take up battle cry as protests continue’, Emma Graham-Harrison and Maryam Foumani, The Guardian, October 5, 2022.

‘Iranian schoolgirls take up battle cry as protests continue’, Emma Graham-Harrison and Maryam Foumani, The Guardian, October 5, 2022.

‘Iran’s Ongoing Protests: Potential Scenarios During a Dangerous Time’, Daniel Brumberg, Arab Center Washington DC, September 30, 2022.